Arriving in Beijing in late spring 1989, I expected bureaucracy and delay. Instead, I found myself inside a city holding its breath. What began as a pause in my travels became a defining moment, dividing my life into before and after, as hope briefly filled Tiananmen Square

I had already been travelling in China for nearly two months, moving slowly across the country, notebook always in my pocket, filing fortnightly travel pieces back to a regional publication in the UK. China felt immense, unknowable, and exhilarating. Still closed enough to feel like a privilege, still poor enough to feel raw.

Beijing was meant to be a pause rather than a destination. I was waiting for a visa to Pakistan so I could travel home the long way west through Xinjiang, across Kashgar, and along the old Silk Road routes that had fascinated me since childhood. I expected bureaucracy, queues, bad tea, and boredom. Instead, I walked into history.

The city itself felt restrained, almost hushed, as if holding its breath. Wide avenues filled with bicycles rather than cars. Men in Mao jackets. Women in sensible shoes. The air smelled of coal smoke, dust, and cooking oil. It was not an unfriendly place, but it was cautious. China in 1989 was opening to the world, but not yet comfortable with it and foreigners like us were still curiosities.

As visitors, we were required to stay in government approved hotels. These were functional, anonymous buildings with hard beds, thin towels, and staff who observed you carefully while remaining unfailingly polite. Payment was in Foreign Exchange Certificates (FEC), rectangular, pastel coloured notes that had to be used by foreigners, that existed alongside the local Renminbi (RMB) but never truly mixed with it.

Officially, FEC and RMB were exchanged one to one. Unofficially, they were worth far more. Outside the hotel gates, an army of elderly women, tiny, sharp eyed, and endlessly patient waited to whisper and gesture, ready to exchange your FEC for local currency at almost double the rate. They wanted FEC to buy imported luxuries in government shops foreign cigarettes, soap or a Mars bar (priced at three FEC, I had one). We wanted RMB to eat, drink, and move around the city like locals.

It felt illicit and theatrical, but it was also simply how things worked. Beer, memorably, was cheaper than mineral water.

During the day, Beijing felt almost timeless. We visited the Forbidden City, wandering through vast courtyards and echoing halls, listening to an audio guide narrated surprisingly by Peter Ustinov, whose wry, amused tone felt oddly intimate against such imperial scale. It was an incongruous pleasure to hear a famous British voice explaining dynasties and concubines to a handful of Western backpackers with cassette players.

We cycled to the Temple of Heaven, its symmetry and calm a counterpoint to the vast political tensions unfolding elsewhere. We travelled by local bus; cheap, crowded, and endlessly fascinating, sharing space with shoppers, workers, and students, all of whom watched us with frank curiosity.

One day we travelled out to a remote, ruined section of the Great Wall, long before it was renovated, restored, or sanitised. Stones lay scattered. Watchtowers were broken and overgrown. There were no souvenir stalls, no turnstiles, no crowds. The Wall felt abandoned to wind and history. We climbed it alone, aware of its scale but also of its fragility as an empire’s confidence slowly crumbling back into the hills. It felt like a metaphor, though I wouldn’t have dared say that aloud at the time.

What truly animated Beijing that spring, however, were its students. They were everywhere; on buses, in cafés, in parks, in cheap restaurants where we ate noodles and drank warm beer from thick glass bottles. Whenever we sat down, someone would approach. Sometimes one student. Sometimes three or four. They wanted to practise their English, yes, but more than that they wanted to talk.

They asked about Britain, about travel, about music, about our life. They spoke about the future with a mixture of excitement and frustration. China was changing, they said, but not fast enough. They talked openly about corruption, about hope, about the need for reform.

The protests had begun following the death of Hu Yaobang, whose reputation as a reformer made him a symbol far larger than the office he once held. His death had given the students a rallying point, a reason to gather, to speak, to be visible.

What struck me most was their optimism. This did not feel like rebellion. It felt like belief.

Yet the mood could change in an instant. Occasionally, in the middle of a conversation, the students would suddenly fall silent. Chairs scraped back. Bodies shifted away. Government officials or men who looked like them would enter the room. Nobody stared. Nobody challenged. Life simply adjusted around their presence. The message was unspoken but perfectly understood.

On 13 May 1989, I went to Tiananmen Square. By then, the protests had swelled to extraordinary numbers, hundreds of thousands of people gathered in the vast space, banners raised, voices lifted, tents pitched on the stone. The scale was overwhelming. Students, workers, even families. This was not a fringe movement. This was a city speaking.

Police attempted several times to stop me reaching the square. There were barriers, diversions, vague instructions to turn back. But the crowds were too large, too fluid. Eventually, like everyone else, I was simply carried forward.

That day, around 300,000 protesters gathered, there to support the students who were starting a hunger strike in an effort to force the Government into negotiation. The atmosphere was charged but peaceful. There was music, chanting, speeches shouted through crackling loudspeakers. Students lay on stretchers under makeshift awnings, watched over by friends and volunteers. There was nervousness certainly but also determination. A belief that being seen mattered. That the world was watching.

I remember thinking how brave they all were. I also remember thinking naively that this would have to end well. That a government could not ignore this many voices. That reason would prevail. History, of course, had other plans.

The following evening, 14 May, the authorities decided my presence in Beijing was no longer desirable. There was no drama. No explanation worth repeating. I was driven to the station, a film was carefully removed from my camera and I was put on a train to Xian, away from the capital, away from the square, away from whatever was about to happen next. It was done efficiently, politely, and without argument.

At the time, I was irritated more than alarmed. I assumed this was a precaution. A way of keeping foreigners at arm’s length while things settled down and ensuring that their version of events was the only one. I had no idea that martial law would be imposed days later. No idea that tanks would roll into Beijing. No idea what the night of 3 June would bring.

Once I left the city, news became fragmentary. China was large, slow, and opaque. Radios crackled. News came from the Government and there was no news.

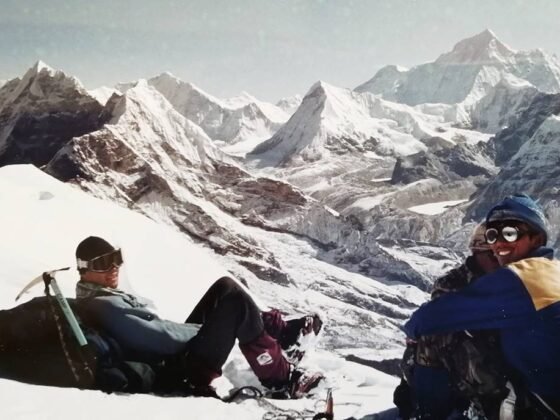

I was in northern Pakistan, listening to shortwave radio, when the reports came through. Gunfire. Tanks. Students beaten, arrested, killed. The scale of it was unimaginable. The language on the radio was cautious but unmistakable. Something terrible had happened. Something irreversible.

What haunted me most were not the headlines, but the faces. The students who had shared their hopes over cheap beer. The young men and women who had asked about Britain, about the future, about what freedom felt like elsewhere. I had walked among them. I had listened to them speak. And now I had no way of knowing what had become of them.

Time has not softened those memories. Beijing in 1989 was not just a destination. It was a moment suspended between possibility and repression. A city where the past loomed large, the present felt fragile, and the future briefly felt negotiable.

As a young traveller, I didn’t fully grasp the risk those students were taking. I didn’t understand how rare that openness was, or how quickly it could be crushed. I only knew that something extraordinary was happening and that I was lucky, and uneasy, to be there. Travel often teaches us about places. Occasionally, it teaches us about power. Beijing, that spring, taught me both.