I gazed enviously at a taxi-bus as it screamed by on a narrow twist in the road. A hot breeze gushed through its open windows, caressing the passengers. Even the goats tethered precariously to the roof rack seemed to gloat as they passed our bumbling bus. The seals on our windows were rigid, although there appeared to be little possibility of the air conditioning ever working. Hot, sluggish air filled my lungs with every breath and the fawn-coloured plastic seat was fast becoming a second skin.

We had been on board for eight tortuous hours and weren’t even halfway yet. I consoled myself: at least we had daylight, which was one up on the chickens scratching around in the baggage compartment.

Our bus stopped often. It stopped for anybody on the road between Ségou and Mopti. The aisle casually filled with people sitting on upturned buckets. Women wearing vibrant headscarves formed a psychedelic rainbow beside me. Curious children passed the time quietly staring, not daring to slip a smile, even at the dusty driver’s now ginger Afro. Roadside merchants preyed on us, cajoling with huge wedges of fleshy watermelon balanced precariously in reed baskets on their heads.

My neighbour, six foot two, flowing blue caftan, beautiful smooth coffee-bean skin, proved to be an ardent shopper. At one stop he purchased six whole watermelons, which were stowed haphazardly in any vague space (my space), making movement virtually impossible.

Our bus also stopped for Allah. At this pace, we were likely to witness all five daily prayers. Loud, intense discussions reverberated around the small hot space; perhaps people were debating the inconvenient watermelons, or the red-faced tourists. Closing my eyes and squeezing heat and dust from my mind, I pictured a large airy room, a vast welcoming bed with crisp white linen and a ceiling fan slowly revolving above me…

It was four-thirty in the morning. We had arrived in Mopti several hours earlier. The call to prayer resonated through the early air, stirring my erratic slumber. The staccato of a dripping tap and the scuffle of livestock outside our drab cell of a room accompanied the muezzin as he continued to call the faithful: Prayer is better than sleep, Allah Akhbar…

Distressed, I considered my options. I could attempt to stop the dripping tap – though that meant dicing with the squads of mosquitoes lurking in the gloom. The room’s mosquito net was something of a relic: a yellowing lattice held together with Elastoplast, the most fragile of shields. My options weren’t looking good.

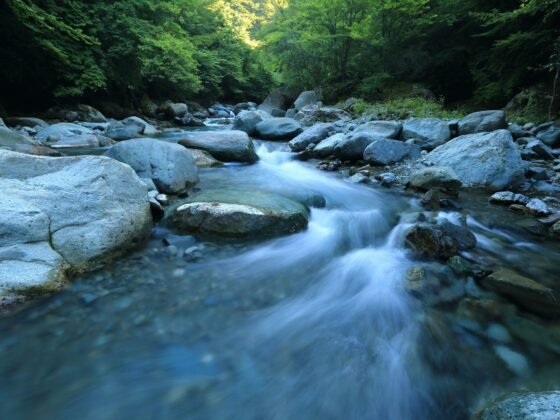

Later that morning, grateful for daylight, I stood on the shores of the Niger River, blinking sleep from my eyes. I was talking with the captain of a grain and cereal pinasse.

A boat.

It had to be an improvement on the bus, didn’t it?

Then I saw the dark hulk brooding in the shallows. A hive of activity buzzed on board as the crew prepared to leave at a time casually nominated by the beaming captain. We quickly settled on a fare of 15,000 CFA (about £20). The captain’s mate – swathed in oil-soaked clothing and studying us closely – would sort out a prime spot in the bow with a clean grass mat for another thousand. A shake of hands sealed the deal.

The journey to Timbuktu was said to take three days, give or take one, and we were advised to bring food and water for the duration. A pirogue ferried us out to the boat, slung low in the water and now even heavier with canned sardines, fresh bananas, and the ultimate river accessory: a shocking pink mosquito net.

We cast off around one o’clock, lounging on our bed of lumpy grain sacks. Serenely, we floated away from the chaos ashore, the throngs of people, children whispering cadeau?, the sickly tang of over-ripe pineapple fused with dried fish. In contrast to the teeming markets, the river lay broad and beautiful, beckoning us onward.

The bow was peaceful: the soft flutter of a shabby ensign, the hypnotic voice of a man telling Islamic stories, the swish of the ragged hull in the water. The crew worked enthusiastically, greasing heavy chains that ran to the rudder and pulling on a string suspended in the reed canopy above us to communicate speed to the engine room.

“The telephone,” the captain explained was a crucial communication device, not, as we had first thought, a handy place to hang grubby sandals.

Beyond the boat, life unfurled. Dragonflies skimmed the water, flocks of birds followed our wake, and pinasses with cereal-sack sails headed home along the riverbank. Huge mud mosques appeared from nowhere. Doum palms punctuated the shore, each an important beacon for fleets of colourful fishing boats, lovingly inscribed with the year of their creation.

As the sun sank, the vivid colours of day melted into the river and a great calm wrapped itself around our boat. We watched as zebu came to lap at the water’s edge and the last fishermen cast their nets beneath a bruised sky.

Night brought little sleep. Wind whipped up and water splashed over the low bow, saturating our sleeping bags. Periodically we stopped to drop off goods, torches catching flashes of bright white teeth in the velvet darkness, steaming wafts of sweet tea rousing us.

At dawn, near Diré, a family ran excitedly down the bank to collect a mammoth watermelon tossed overboard and drifting slowly towards them. Hitching their voluminous skirts above their knees, they rushed to embrace the precious cargo.

The sweeping dunes of the Sahara were gradually swallowing the lush green of the Niger floodplain. Our voyage was drawing to an end.

This unpredicted speed robbed us of the dawn arrival we had hoped for. Instead, we reached the insalubrious port of Korioumé just as residents, and swarms of mosquitoes, were settling down to dinner. We were quickly told that no taxis operated at this hour.

A local man soon approached us. A torrent of French hyperbole followed, promising moped transport into Timbuktu some 20 kilometres away. He assured us safe passage, for a good price of course. I was relieved, though dubious, when his friend arrived with a second moped.

Reluctantly, I clambered onto the clapped-out 250, backpack strapped tight, my husband disappearing around the corner of the port. My chauffeur’s turban slowly unravelled into my face as we rattled down the dusty road beneath a glorious canopy of stars.

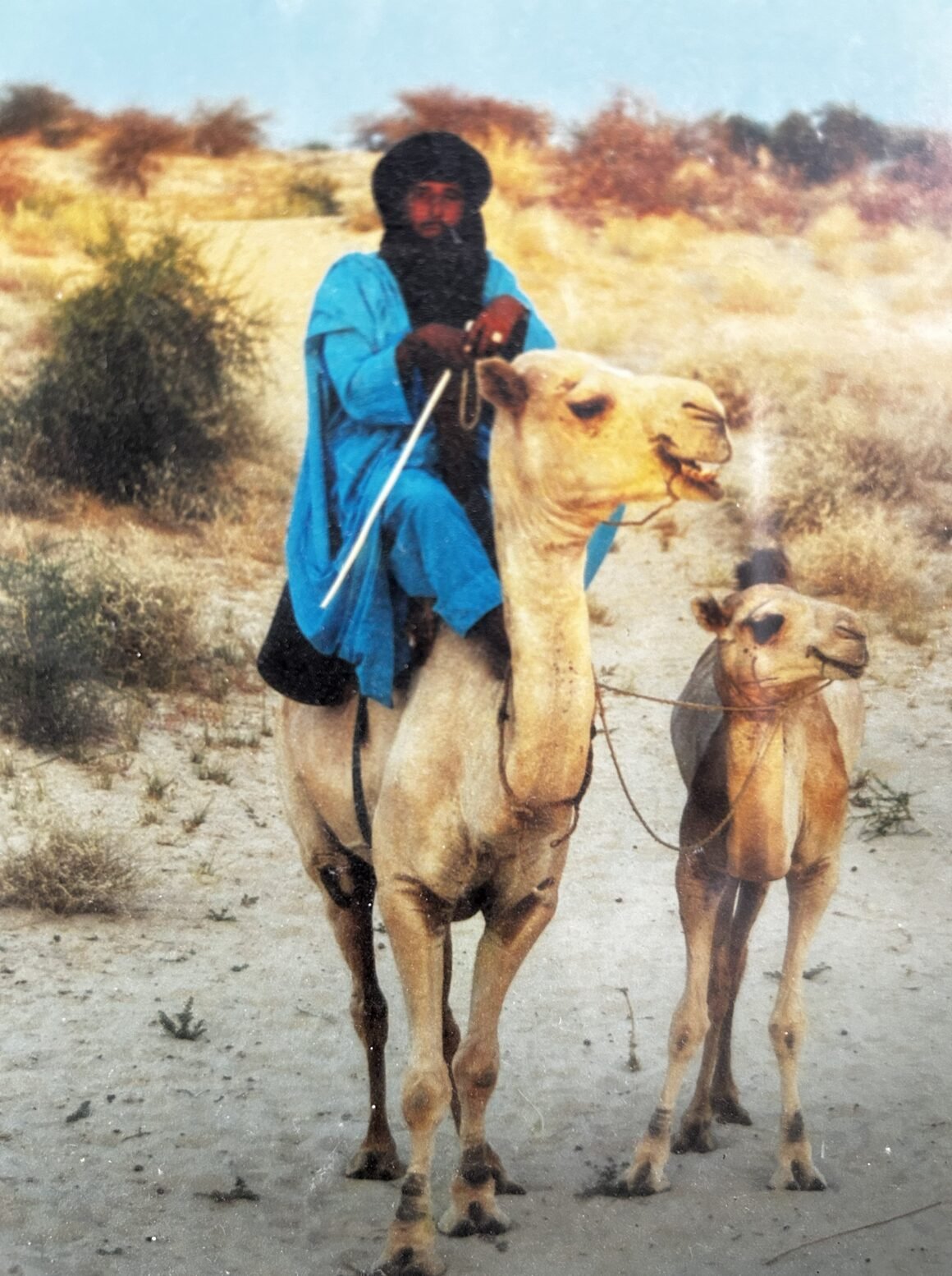

Downtown Timbuktu is a muddle of sandy streets. The Tuareg, nomadic people of the Sahara , have a strong presence on the edge of town, and it was here the next day, huddled around some camels, that we met our host for the next few days.

He was elegantly dressed in a turquoise blue cape, a skilfully wound black scarf framing his face. His features, furrowed like the desert dunes, had an opalescent quality. He rested his bare feet expertly in the dip of his camel’s neck. There would be no forgetting his name: Sandy.

Into the proverbial sunset we rode, saddle-sore before nightfall on day one. There was no point attempting to emulate Sandy, who barely appeared to hold on as he trotted away from Timbuktu, his giant gold wedding ring glinting in the weakening sun, a guiding light in the unfamiliar shifting sands.

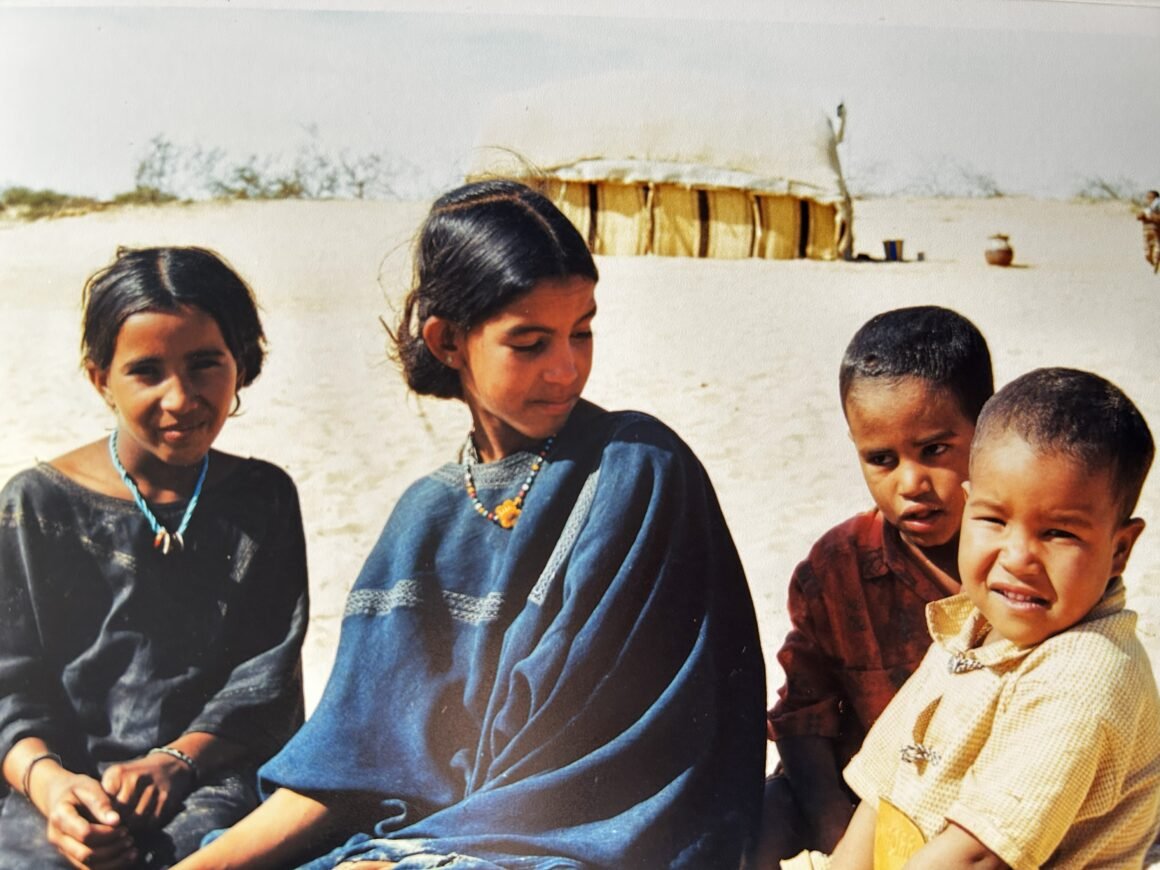

Eventually his children greeted us in the darkness. Home was a rectangular hessian tent with bold charcoal stripes. A strengthening breeze billowed inside, puffing the roof like a freshly cooked soufflé. A large hand-painted terracotta pot sat at the entrance, suggesting permanence. There were at least five children. The girls wore dark navy tunics with delicate white embroidered yokes, tiny multicoloured beads strung around their necks.

Rugs were laid on the sand by a thicket for dinner. From a large battered pan came a steaming mound of milky goat-meat curry. Each mouthful was chewy, gamey, and accompanied by the unexpected – authentic Saharan sand.

After supper we unrolled our sleeping bags. The night sky looked different here. Like studying a work of art.

At dawn, bleating goats woke us to a soft orange glow. The homestead revealed itself fully: nothing discernible, really, but sand and scrub in all directions. It was unnerving. I felt besieged by sand.

Breakfast arrived on a tray: dried dates, biscuits, boiling water. In a small dented tin with the familiar N of Nescafé still just visible, we found precious granules of instant coffee. The dates were surprisingly filling, possibly due to the healthy population of maggots discovered three dates from finishing.

I can’t say I bonded with my camel, nor did I grow to love Arabic tea, drunk in the customary way: black as hell, strong as death, sweet as love. But it was a pleasure to watch Sandy prepare it, lifting the teapot skywards and pouring with astonishing precision into a tiny cup, passed around for all to share.

During one tea break, a camel broke free from its hobble, when two legs are tied to limit roaming, and bolted. Its owner gave chase amid much snorting and gesticulation, to Sandy’s great amusement. The camel eventually capitulated, lured by the oldest trick in the book: food.

Leaving Timbuktu was thankfully not by camel, bus or pinasse. We opted for the relative speed and comfort of a Land Rover, complete with driver and navigator.

Even this was not straightforward.

The journey began well, until we reached the river. Moored where the road petered out stood a rusty ferry, painted Tuareg blue. The river looked narrow; the crossing should be brief.

It was shorter than anticipated.

We walked aboard while our driver parked. The ferry chugged into mid-stream, low in the water with half a dozen vehicles. Two-thirds of the way across, it shuddered and stopped – grounded.

People flocked back to their vehicles as the bow gate was lowered. An elected runner splashed into the water and bounded ahead, finding the safest route across the riverbed. Cars were waved off one by one.

We followed. The engine groaned as we plunged into the water. Waves sloshed over the bonnet, windscreen wipers sprang into life, and I clung on, eyes fixed on the car ahead.

We rocked around for a moment. Then with an almighty surge we leapt forward as the tyres seemed to find some solid ground.

This journey took place in 2000. The FCDO advises against travel to Mali at the current time due to security concerns.