It was 1985, and I was 19. I’d been travelling around India for 4 months and was at the end of my trip, existing with a rucksack full of dirty laundry, a fraying Lonely Planet, and the vague hope that something unexpected (and free) might happen. I’d just arrived in Bombay (now Mumbai), jaded, broke and heat-dazed, a couple of days before, ready for my flight home to the UK. I’d sold my Walkman a few weeks earlier in Jaisalmer, a very tradable item in those days, and that money had got me this far.

I wandered the city looking at the sights, eking out my last pocketful of rupees at street food stands when the unexpected happened. A well-dressed lady in a dazzling green sari approached me outside the Gateway of India and asked if I wanted to be in a film at 60 Rupees per day. Initially I thought it was a joke, a scam, maybe, but curiosity, and hunger, won out. What did I have to lose, certainly no cash. I said yes and the next morning, I found myself outside a large colonial-era club building, where a Bollywood crew was shooting a scene for a film called Mard, starring someone named Amitabh Bachchan.

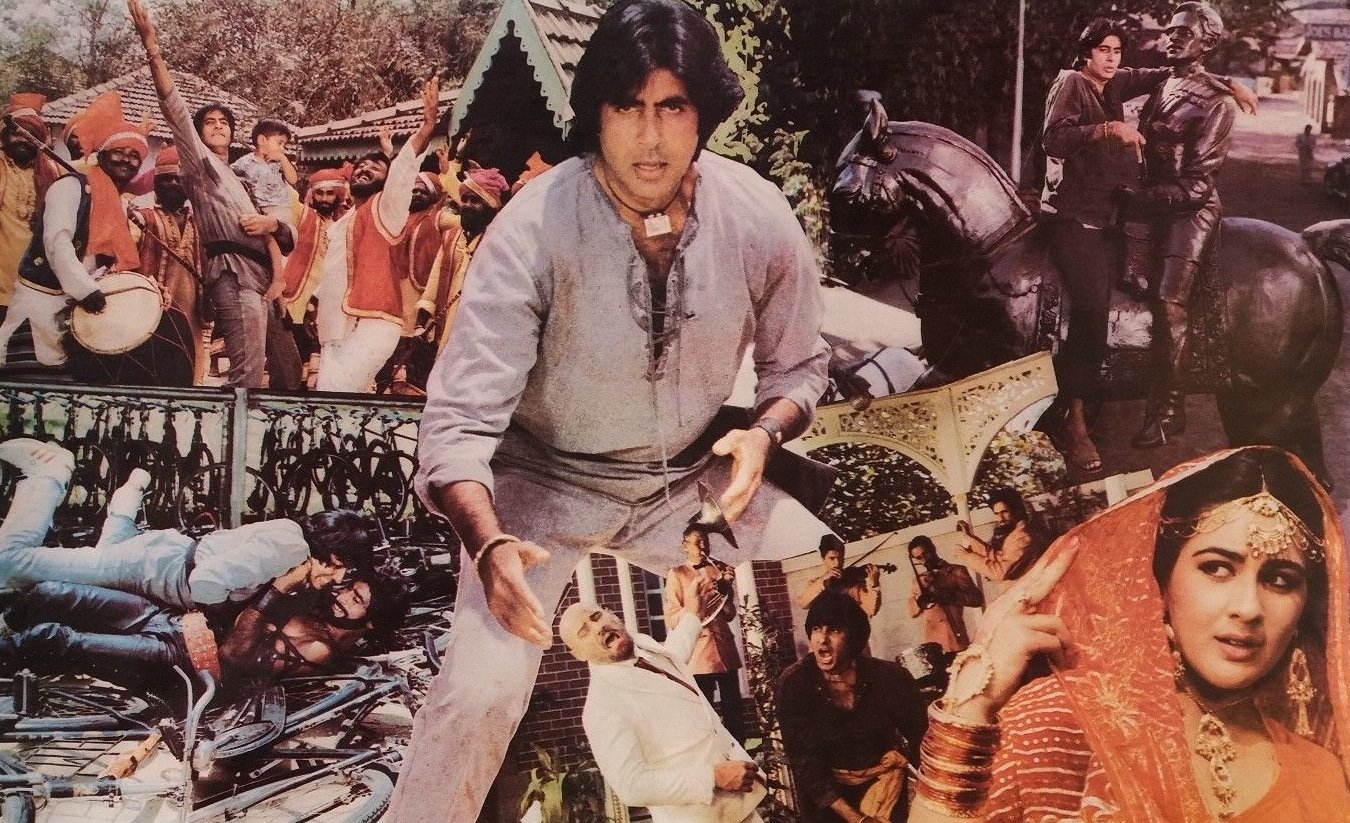

I didn’t know it at the time, but Mard would go on to become one of the biggest hits of 1985, a classic of its genre, a full-throttle slice of patriotic masala cinema complete with horse chases, tearful reunions, British villains, and absurdly muscular heroics. And for a couple of surreal days, I was part of it.

Dressing the Part

Costume came first. A man waved me over and handed me an outfit that made me laugh out loud: a pair of bright white trousers, a white button-down shirt, and a comically wide floral tie. To top it off, they gave me an enormous, garishly checked blazer, something between 1970’s car salesman and eccentric golf club member. “Very British,” someone said, approvingly. After 4 months I was just happy to have clean clothes on.

The film was shooting a scene set in an elite British club during the Raj, a heavy-handed parody of colonial life where English officers lounged around a pool, sipping drinks, playing cards, and sneering at the natives. We, the extras, were the background “British” characters. There were about forty of us from a patchwork of countries, mostly tourists or expats in Bombay for one reason or another, all temporarily cast as symbols of imperial decadence.

We sat around the pool, with whisky tumblers in hand filled with watery Coca-Cola to mimic the real thing. We were instructed to nibble at crisps using knives and forks, to give an air of absurd refinement. The real scene-stealer, though, was a large wooden sign that read: “NO DOGS OR INDIANS.”

The Heat, the Lights, the Madness

Filming took place under what felt like a burning sun. I counted at least seventeen huge reflectors set up to bounce the Bombay sunlight directly onto the poolside set, along with six monstrous spotlights. The combined heat was staggering. Sweat trickled down our necks. Makeup artists dabbed at the principal actors between takes, but we extras were left to shine on our own.

Despite the discomfort, the energy was high. There was an excitement in the air, a feeling of being part of something chaotic, theatrical, and utterly Indian. The director, Manmohan Desai, was a ball of energy, striding between cameras and yelling orders with the confidence of a man who knew his audience. Everyone seemed to like him but always did exactly what he said.

Enter Amitabh

Our cue was simple: when the character Raja Azaad Singh came into the club to collect money from rents being withheld by the British and is mocked by the club members, we were to laugh. When one of the British officers then forces him to drink whisky, we were to laugh harder.

Then came the moment we’d been waiting for: Amitabh Bachchan’s entrance. I didn’t know who he was, but the crew’s reverence made it clear he was a big deal. Tall and charismatic, Bachchan walked on set to applause, already in character as Raju, the whip-smart, muscle-bound tonga driver. It was very dramatic as his tonga crashed through the club gates, driving straight into the pool, horse and all. It was repositioned carefully; Bachchan climbed in and the scene started as he pulled his head from the water

He performed the scene several times with slight variations. In one take, he spluttered and coughed theatrically; in another, he roared like a lion. Each time, we had to act amused and disdainful, sipping our fake drinks and pretending to find it all highly entertaining. In the final cut, the scene is comic, satirical, and symbolic, a reversal of colonial power in true Bollywood style. At the time, it just felt hot and vaguely ridiculous.

But watching it now, the scene stands out for its cheeky defiance. Mard isn’t subtle, it revels in its caricatures. But in 1985, for an Indian audience raised on tales of colonial injustice, there must have been something cathartic about watching their hero stride into a British club and wreak poetic justice.

Lunch with the Stars

Around 2 p.m., we broke for lunch. I expected to be herded away to some back room, but to my surprise, we extras were invited to join the rest of the crew and cast in a shady courtyard out back. Metal tiffins were laid out on long tables, steaming with chicken curry and rice. I sat cross-legged eating with my hands alongside assistant directors and supporting actors. Even a few of the main cast came by to say hello, warm, curious and entirely down to earth.

Someone introduced me to Amrita Singh, who played the love interest in the film. She was funny, sharp, and intrigued that a random teenager from England had ended up in their movie. I didn’t know at the time that she was a rising star, only that she was friendly and seemed to find the whole shoot as amusing as I did.

Looking Back

I only worked on Mard for two days, but the memory has lasted four decades. The day after filming I flew from Mumbai home to the UK, using the last 20 rupees of my film fee to take a rickshaw to the airport. Life continued. I finished university and fell back into normal life. But every now and then, I’ll find a grainy YouTube clip of the club scene and there I am, a slightly dazed young man in a monstrous jacket, sweating in the background as Amitabh Bachchan saves his father from a villain in a British army uniform.

I’ve learned more about Mard’s legacy. It became one of the highest-grossing films of the year, cementing Amitabh’s status as the ultimate Bollywood hero. The soundtrack, composed by Anu Malik, spawned hits like “Hum To Tambu Mein Bamboo” and “Mard Tangewala.” And Manmohan Desai, already a legendary director, added another blockbuster to his string of patriotic extravaganzas.

To this day, Mard is remembered for its over-the-top energy, iconic one-liners (“Mard ko dard nahin hota!”), and unshakeable belief in the triumph of good over evil, no matter how ludicrous the plot.

And for me, it will always be the film where I wore the worst jacket of my life, sweated under seventeen reflectors, and got my fifteen seconds of fame in a Bollywood classic. All because I happened to be in the right place, at the right time, with a British passport and a willingness to look ridiculous.

You can watch the scene I was in by clicking here – opens in a new window.