By Stefani Leonard

PureTravel Writing Competition 2024 – Longlisted

I walked past Tsweleni Tavern, a tiny bar on South Africa’s Wild Coast, every day for six days. Boys played cards inside the open garage-like building, women shuffled in and out of the tiny corner shop carrying candles, groceries and loose change. Men snickered and women rolled their eyes; children kicked soccer balls around while fathers drank warm beer. It was both wildly familiar and strangely unrecognizable.

On this particular day, however, the tavern was empty. Aside, of course, from the owners: a woman cloaked in a loose dress and a tarnished head covering, and a man holding a tiny baby, no more than a few months old. The man sat on a step outside the corner shop while the woman, oblivious to my existence, hummed a tune inside.

I walked in between my friend Lauren and village local Tayoona on our way back from the beach. We were still about a five-minute walk from Tayoona’s homestay; the tavern was the halfway point between the beach and our final destination.

While Tayoona and Lauren continued conversation, I took notice of the man and his baby girl: the tattered clothes she wore, and the tiredness painted on her father’s face. He bounced his daughter on his lap and hummed along to the muffled song his wife sang inside. I admired the joy on his baby’s face and slightly envied the love I felt emanating from father to daughter—I missed my own father, my mother. The scene before me reminded me that love, in all its forms, is a universal language; we all do it, we all crave it, we all miss it when it’s gone.

I couldn’t help but stare.

But then I coughed, accidentally and a bit too loud, and the baby broke her father’s gaze and tilted her tiny head in my direction. Immediately, she wiggled her tiny finger at me. She did this, back and forth and back and forth, until her father (after an exasperated breath I wasn’t sure I was meant to hear) beckoned me over. Hesitantly, I complied.

“Molo,” he called when I was at a respectable distance.

“Molweni,” I responded, proud of myself for remembering the proper greeting. Tayoona and Lauren followed sharply, silently, behind.

“She’s sweet,” I said, now only a few feet in front of the two. I smiled warmly at the baby girl.

“Your name?” His English wasn’t as orchestrated as some of the other villagers I had previously spoken to, but I understood him, nonetheless.

“Stef.”

“Stef?”

I nodded, smiling once more at his daughter.

“How old is she?” I asked, crouching down at her eye level. She tucked her head shyly into her father’s neck in response.

But instead of answering my question, he peeled the baby off his body and shoved her into my arms. I held her awkwardly for a moment or two as she wailed in my grasp, inconsolable. I tried to bounce her on my hip and coo a few words of encouragement, but nothing was working. She only grew louder.

Obviously flustered, I glanced at her father for support. As he registered the fear on my face, he exhaled a lighthearted chuckle before rescuing me, tucking the child back into the crease where his jawline met his neck.

“Sorry,” he laughed. “She’s afraid of white people.”

I nodded, lips tight. I felt the space was best filled by silence, for words could never truly say what I wanted them to. “I’m sorry,”I might try. Or “it’s okay, I understand.”But, then again, how could I understand?

**

On May 20, 2024, I boarded a plane alongside sixteen fellow college students, two professors, and the Dean of Arts and her husband—all, at this point, virtual strangers.

This trip consumed me long before it even began. I spent six months—from the moment I signed up, until the moment I boarded the plane at Newark International Airport—in a constant state of anxiety. I didn’t want to go; it was as plain as that. Even just thinking about being in a tiny aircraft for fifteen hours left me feeling claustrophobic; I didn’t know what I’d do with myself if I couldn’t go on a run for three weeks, was plagued with questions of “what if?” What if I fall terribly ill overseas and am left to fend for myself in a South African hospital? What if all my travel companions hate me and it’s the loneliest three weeks of my life? What if I can’t sleep? Can’t eat? What if everything goes wrong? What if it doesn’t?

How to pretend I’m excited; I was exhausted.

The flight was about as bad as I expected it to be, of course. I didn’t sleep, was stuck next to a man who kept insisting I “sleep on his shoulder” and in front of a passenger who stretched their legs so far in front of them, that I kept bumping my heels into their toes. My stomach was doing somersaults—either out of anxiety or from the mysterious pasta dish I ate at the beginning of the flight, I wasn’t sure. Nonetheless, it was a persistent pest. I got up to pee more times than I could count on one hand and no movie could distract me long enough to ignore the loud grumbling beneath my sweatshirt.

Eventually, though, the lights in the cabin came on; we were two hours out. Two hours, I told myself, was nothing. I’d already made it thirteen restless hours, what’s another two? The man next to me slurped loudly on two cans of Sprite—one after another. He slopped down his breakfast, spitting onto the tray table as he did it. If my stomach hadn’t already been causing me unease, it certainly would’ve been by then.

Two hours. Just two hours.

I put my headphones on, pressed the only playlist I’d downloaded from Spotify, and let the music guide me into a vibrational state of unawareness. I was, for the first time all flight, relatively calm; not quite excited, but finding it easier to pretend.

We’d be there soon; it was either look forward or die pedaling backwards. The choice was mine, but not really. Because, really, what choice is ever innately ours to make? That is, a decision never influenced by external forces; can you recall an example in your own life?

I can’t—I don’t know if it’s ever been that simple.

I kept going, even if only for the fear of falling behind. I kept—keep—going. Don’t we all?

Our trip started in the bustling city of Johannesburg. A once affluent gold mine, the city was vibrant with opportunity, but—as are all cities—it was also stricken with quite a lot of poverty. When I told people I was studying abroad in South Africa, specifically that I was spending my first couple of nights in Johannesburg, I heard almost a resounding echo of cynicism.

“Really? This was your first choice?” My mother wondered aloud when I told her over the phone in late December.

“Yes,” I responded as firmly as I could muster. “It looked really cool. Outdoorsy, and stuff.”

“You hate the outdoors,” my mother pointed out.

I rolled my eyes. “No, you hate the outdoors.”

“Right,” my mom huffed sarcastically on the other end. Obviously biting her tongue to avoid pointing out what she—and though I wouldn’t admit it, I— believed to be true; I’d never, ever survive for three weeks that far away from home. Let alone in a developing country. “But if this is really what you wanna do, you know Dad and I are happy for you.”

I hung up shortly after—only after assuring her I’d cover the cost, if that’s what she was worried about.

“I’m only ever worried about your safety,” my mother rebutted. “Is this safe?”

“Yes, it’s safe,” I said through gritted teeth, half-lying, half-truthful. The lie being I knew only as much as my mother did. The truth being I assumed—like I do with most things—that it would be fine. It had to be fine.

And those first nights in Johannesburg were fine. We stayed at Curiocity Backpackers with some of the most considerate hosts I’ve ever had—on the first morning, the man making our coffee went out to the corner store to buy almond milk just because I had asked if he could make me an almond milk cappuccino. He didn’t ask questions, he didn’t hesitate, he only said: “Yes, yes give me one minute.” And then he was gone, quicker than I could understand what had just happened. He returned ten minutes later with a bag of three cartons of almond milk.

“Almond milk,” he declared as he pulled them from the plastic bag. “For you.”

On our second night in Johannesburg, Tanya, one of our many hosts, took us to a little restaurant down the street that was hosting karaoke. Just for us—the Americans.

As I sat in a chair, directly across from a projector, the words to American songs lighting up the screen, voices familiar and unfamiliar coming together in perfect harmony, I couldn’t help but smile. I sipped my chai tea silently, absorbing the scene in front of me—several of my fellow American students performing, arm-in-arm, with Johannesburg locals, sipping on beer, wine, tea, coffee, whatever—it wasn’t what we were drinking that mattered, it was what we were doing. Wherewe were doing it.

I was in South Africa—it hit me all at once. I was in South Africa, singing karaoke in a bar full of strangers, enveloped in a feeling I could only describe now as gratitude. I was really doing this thing. Really, truly, doing it.

“Hey,” I nudged Lauren’s shoulder, careful not to knock the hot cup of tea from her hands. “I don’t think I’m pretending anymore. I think I’m having fun.”

Lauren smiled, nudged me back. “Me too, I think.”

On our final day in Johannesburg, we were allotted quite a bit of free time. A few of us decided to wander into town—I needed socks, as I mistakenly only packed four pairs, and the others were on the hunt for the perfect souvenir to bring home.

That afternoon, I was dressed in a white tank top, cropped slightly above my stomach. My belly button hung out, I remember, and my shorts hugged my waist a bit tightly. When I walked too quickly, my shorts rose slightly beyond comfort. But it was hot—I didn’t want to be sweating if I was going to be doing all this walking. It made sense, of course. It made sense to me.

We were chased down the street that day by a man who went by the name of “Sweet Potato.” He was an artist—one we had met briefly on our first morning in the city. A few girls commissioned him, complimented his unique style. I remember being struck by the collaboration of colors, the faceless women dancing in a line across one particular canvas.

“Can I ask what’s happening in this one?” I asked him that morning, pointing to the faceless women.

He smiled, grabbed my hand: “Come,” he said, tightening his grip, pulling me into his chest, giving me no choice, really, but to comply.

He smelled of sweat and, faintly, of dried paint. We danced for only a few moments before I pulled myself away, thanked him politely with a small smile.

“Tinga Tinga,” he said, amused; this, I assumed, was the name of the dance. He bowed playfully in front of me, waited for my laughter before lifting himself up again.

But, when we saw Sweet Potato again, it was not to dance. He chased us, ordering one of our girls—Adele—to come back and talk to him. Whether out of instinct or fear, I still can’t be sure, but the rest of us ran. We ran as fast as we could, searching the crowded streets of Johannesburg for a familiar face that could help us. But there was no one.

My voice, ringing in my ears—shaking, rattling. I am in South Africa, I thought, over and over again. I am in South Africa and there is nothing I can do. No one I know, no building I know to be safer than another, no safe word—no. Nothing I can do.

Adele eventually caught up to us, free of Sweet Potato, laughter her only coping mechanism.

“That was fucking nuts, dude,” she gasped. “What the fuck?”

Later that day, we’ll retell the tale to a man we met back at Curiocity—my friends and I took to calling him Mr. Miami, since he never did tell us his real name, only that he was born in Miami, Florida. Mr. Miami was in Johannesburg on a business trip; he had just arrived from Cape Town, and to say he was bitter would be the understatement of the century. He was miserable; he spent most of the hour we spoke to him recounting everything that was “better” in Cape Town—the food, the people, the hostels, the air.

“Have you all been?” he asked.

We shook our heads.

“The vibe,” Mr. Miami said, “was just much, much different there. You’ll see. Johannesburg,” he gestured at the noise behind me—the streets with vendors, the yelling children on their way home from school. “It seems great right now because you’re here right now. But—fuck, I had some of the best Italian food I’d ever eaten.”

One of us explained that our group is on a study abroad trip. We are going to Cape Town, but not for a while.

“Two weeks,” one of us said.

“About,” I agreed, my voice etched with warning. Our group was advised to not relay our private itinerary to anyone. And though we knew it—understood it, even—we often—very often—forgot.

“Wow,” he mumbled. I couldn’t quite recognize his tone—bafflement or admiration. I settled somewhere in between both. I guessed that Mr. Miami was the kind of man that never had to explain why he thought what he thought; what he thought was merely what was. He was that kind of guy.

“So, this Sweet Potato character,” he continued, rubbing the stubble on his chin. “You guys were dressed like that?”

My friends and I looked down at our outfits—tank tops and athletic shorts. We shrugged, offered a weak nod of our heads.

“Well, no wonder he chased you all.” Mr. Miami cast a judgmental look at Lauren, shrugged his shoulders mockingly back at us. “Blonde hair and blue eyes—you really thought you wouldn’t get some attention on the street? C’mon, girls.”

**

Our time in Johannesburg came and went—three nights, two days. I was excited for a change of pace; the coast is much, much different, our professor told us. But I live on a beach, so I thought, “different, in a good way.”

I thought I’d be better suited for this pace. Used to it, even. I’ll be fine; if I thought Johannesburg was easy, I was going to thrive on the wild coast. At least, that’s what I told myself.

I live at the Jersey Shore—it’s loud, overcrowded, manicured and polished to perfection. For whom? Of course, that’s debatable. Ask a local and they’ll tell you it’s all for show; ask a tourist and they’ll tell you it’s the most magical place they’ve ever been. The lens has always mattered more than reality.

But in Tsweleni Village, I had to look through a lens I’d never used before. An observer, a visitor. I struggled making similarities out of nothing—but try, I certainly did. It was a pathetic effort to feel more at home.

“Oh, falling asleep to the sound of the ocean,” I thought the first night. “This is vaguely familiar.”

“The smell of saltwater,”

“The wet sand beneath my callused feet,”

“The sunrises,”

“The sunsets,”

“The beach,” I thought. “The beach—maybe different from mine—but all on the same Earth.”

And finally: “This might be the closest I’ll feel to ‘at home.’ And I’m miserable.”

I struggled in Tsweleni Village. There was no running water, and the water we were privy to was strictly rainwater—collected from the runoff stream built into the crevices in the sidewalks. We slept in straw huts, prone to spiders and other creepy-crawlers. I was out of my depths—for sure.

But I am also stubborn—more than most. My mother’s doubt rang in the back of my head. I refused to let her be right; I refused to waste a once in a lifetime opportunity at the hands of uncertainty.

How does the saying go?

“Life begins outside of our comfort zone.”

I scribbled that quote—over and over and over—on the tattered pages of my journal. Every time I caught myself panicking, homesick, miserable, I wrote. I wrote it so many times, it felt like the quote belonged to me; not just for me.

It wasn’t that I didn’t expect to be uncomfortable, because I certainly did. But what caught me by surprise was that my discomfort didn’t necessarily stem from that which I expected it to. That is, from the bunk beds I shared with strangers, the short showers that never quite left me feeling clean, the rationed water and unfamiliar foods, the strange rash on my face that, no matter how well I cared for it, just wouldn’t go away. No, it was none of those.

It was easier than I thought, I found, to adjust under that which you have no control over; to accept that, though this may not be your normal, it is someone’s. How to live in someone else’s normal, if for even only a brief week. I could do that—I did do that.

For the most part.

Because no matter how well I coped with bugs, rashes, and lingering dehydration, there was one thing I couldn’t quite stomach. And though it didn’t have creepy-crawling legs, it unsettled me all the same.

On our seventh day in South Africa, our second in Tsweleni Village, a group of about ten of us went for a hike. Our guides, a local man named Api and his friend, Chadley—whom we only stumbled upon by accident as we passed the Tavern—promised us it’d take no longer than an hour—twenty minutes to get there, about twenty minutes to cliff jump into the waterfall (if we so pleased), and twenty minutes to get back.

“No problem,” Api said. “We do this all the time.”

The terrain, after several days of consistent rain, was anything but ideal. We were all slipping and sliding, struggling to keep up with Api’s brisk pace—in a pair of Adidas slides, nonetheless! I forfeited my shoes after about ten minutes, assuring Api that I have tough feet—I walk barefoot at home all the time.

He shrugged, smiled sarcastically. “America,” he said, laughing a little.

Before we hit a mile, two of our hikers decided to turn around, head back to the hostel. Ah, defeated by some mud, we’d all joke. But by about mile three, the rest of us had begun to envy them.

“How much longer,” one of us asked Api.

“Ah, not long,” Api assured us.

“Not long” turned into about another half hour—more, depending on who you ask. Within that final stretch, we were stopped twice. Once, for a local village man who dotted enthusiastically on our “beauty.” He told Api he just wanted one picture with the “American girls,” then he’ll be on his way.

Api, hesitantly, agreed.

“I have no wives,” he told us, as he wiggled his way into the middle of our group. Arms slouched atop the shoulders of two of our girls, he announced, “Ah, America!”

Another time, by a man tending to his land about a quarter of a mile away. He shouted something at Api—in IsiXhlosa, of course, so we could not understand.

“What did he say?” I asked.

Api laughed, glanced knowingly at Chadley.

“He said he wants to marry all of you,” Chadley said, throwing his sweatshirt over his left shoulder. “He offered ten cows.”

“Ten cows?” Lauren asked, a hint of amusement in her voice. She nudged me as we burst out laughing.

Ten cows, I thought. I can’t even convince an American man to buy me flowers on special occasions, but this man—who, for the record, couldn’t have even gotten a proper look at any of us—thought I was worth ten whole cows. The irony of it all was too daft to miss.

“You know,” Api said. “Ten cows is not bad.”

“I don’t need ten cows,” I said. “But I appreciate the offer.”

We walked on for another half mile or so before—finally—we reached the waterfall. But none of us saw a waterfall; none of us even heard water. Before us was a forest of trees—no path, no view beyond the acres of greenery. I thought, for sure, that Api was playing a cruel joke on us.

“I don’t see a waterfall,” I whined, as politely as my exhaustion allowed.

“Hold on.” Api stuck his pointer finger up in the air, already forging his way through the trees. He ducked beneath the dangling leaves, careful not to trip over the discarded sticks stuck in the mud.

He was gone—and back again—before I could ask where he was going.

“Alright,” Api said, climbing back up through the same line of trees he had, only seconds ago, disappeared behind. “Come on.”

“Api,” Lauren groaned, speaking for all of us in our hesitation. “Where are we going?”

“The waterfall,” he said, matter-of-factly.

“What waterfall?” I asked. “We don’t hear anything. Where did you just go?”

“Just come,” Api said, sticking his hand out for me to grab. “I’ll show you. I just saw it. It’s safe.”

Hesitantly, I took his hand.

Api’s definition of “safe” was drastically different from mine; the trek down to the waterfall was along a steep downhill, no clear footpath, no route promising a safe drop off. It was the kind of “path” that, if we had been in America, would have been posted with “No Trespassing” signs and warnings of “Danger! Do Not Enter!”.

I had no idea how Api had climbed down, and back up, in so little time. And without even a lick of sweat on his forehead.

Oh, and my mother! Gosh, my mother—she would’ve had a heart attack if she watched me climb down that mountain.

“Bare foot!” she would’ve exclaimed. “Oh my God, Stefani Ann.”

But, truly, I managed alright. I slipped a little when the mud got particularly runny, but I knew to how to use my bare feet to my advantage—grip the ground with my toes, keep my balance that way.

And that’s how I made it down in one piece. Mostly. Save for a few battle wounds—scratches on either leg, some stretching from my hip to my knee. A little dried blood on the bottoms of my feet. You know, nothing too serious.

“See,” Api said once we’d all reached the bottom, motioning to one of the most beautiful waterfalls I’d ever seen. I remember thinking that the sunlight was hitting the water at just the right angle, giving the falls a glint of sparkle. Magical, I thought. It looked magical.

“Here we are,” Api concluded. And with that, he and Chadley wandered off to a quiet rock in the distance, lit up, and let us be.

I was the first to strip down to my bathing suit.

Lauren looked at me skeptically, but I wasn’t about to jump into a waterfall fully clothed. That would be ridiculous, I told her.

“Do you think they’re looking at us?” Lauren asked, gesturing over at Api and Chadley.

I looked at them briefly, watched as they passed a joint back and forth. Chadley laughed at something Api said. Api then took a long inhale, blew out a cloud of smoke. He passed the joint back to Chadley, watched as his friend sucked in, blew out. An echo of laughter between coughing fits. They smiled, passed on and on and on.

“I think we’re good,” I told Lauren as I took off my athletic shorts. My body now exposed, save for the parts hidden behind my bikini. In South Africa, I found it much easier to wear a mask of false confidence. Because, frankly, I knew my body, and what anyone else may or may not have been thinking about it, was, quite honestly, the least intimidating part of being half-way across the world. I had bigger mountains to climb than my own petty insecurities. Literally.

We swam for about fifteen minutes, another fifteen to dry off in the sun. By the time Api and Chadley had wrapped up their smoke, we were all ready to head back to the hostel.

I dangled my flip-flops from my left hand, clutched my water bottle with my right. Lauren trudged next to me—backpack secure on her shoulders.

“Tired,” Lauren said. This, I knew, was a full sentence. Her briefness, a testament to how we all felt.

“Yeah,” I agreed.

But we kept going anyway, following in step with Api and Chadley. And, for a while, as Api and Chadley lent a hand to the others, Lauren and I had to lead the group.

“Let us take your backpack,” Chadley insisted, tugging at the straps on Lauren’s shoulders after catching up to us. Api hung behind.

“No, it’s okay. I got it, thank you though,” Lauren replied, shrugging him off a bit.

“No, please. It is probably heavy,” Chadley said.

“It’s not that bad.”

“But,” Chadley stuttered, shaking his head. “A woman shouldn’t have to carry that. Please, let me.”

I, feeling Lauren’s agitation in the way her lips tightened, and her chest began to rise and fall in frustrated breathes, assured Chadley we were okay.

“We carry heavy stuff in America all the time,” I told him. “It’s not a problem; we promise.”

Chadley nodded, and though obviously far from appeased, he neglected to say anything about the backpack again.

By the time we’d gotten back up on the walking path, Chadley had taken to trailing behind with a few others, while Api resumed his position at the front of the group—alongside Lauren and me.

“Your feet okay?” Api cast a skeptical eye at my bare and—now—very muddy feet. I could feel the dirt hardening in between my toes; I was equally disgusted, of course, but my ego couldn’t handle admitting that.

“Yup.” I nodded, avoiding eye contact. I could feel Lauren smiling at me, Api judging me.

“Okay,” Api said, shaking his head, but, nonetheless, changing the subject. “Where in America do you all live?”

“Pennsylvania,” Lauren answered quickly.

“Ah, the vampires.” Api nodded solemnly.

“Wait,” I laughed. “No, no. Not like Transylvania. Pennsylvania. We don’t have anything as cool as vampires, I promise.”

“What about alien invasion?” Api continued, his tone curious and without a hint of sarcasm. Lauren and I exchanged uncertain glances before responding.

“What do you mean?” Lauren asked, her disbelief half-heartedly masked beneath her warm tone of voice. She was doing better than me; I couldn’t stop laughing.

“Like, in the movies. It’s always happening in America,” Api answered, shaking his head before stopping abruptly, turning to yell something at Chadley.

“Chadley!” He waved his arms back and forth, waited at a standstill until Chadley had caught up to us. Those who had been walking with Chadley hesitated, hung back. They remained a few feet behind us, close enough to keep up, far enough to continue in their own private conversations.

“Ask them about alien invasions,” Api said to his friend as we resumed walking.

“Aliens?” Chadley was just about as puzzled as Lauren and I were.

“Yes, like in the vans!”

“Oh,” I said, nodding my head. That’s all it took; it clicked. Api was not talking about alien invasions—he was, I think, referencing sex trafficking. “I think I know what you’re talking about. But, um, that’s not aliens. It’s actually just some really bad people, doing some really bad things.”

And at that, it seemed the same realization had hit Lauren. How best to explain this—we were both at a loss.

Api and Chadley waited patiently for our explanation—if not aliens, then what? We could see the question behind their eyes, their skepticism in the silence.

“It’s more like,” I struggled to find the right words. “Kidnapping. Like abduction? But not by aliens. By people of other people.”

“Ah,” Api said awkwardly, glancing sideways at Chadley. It was a cultural divide I hadn’t quite anticipated.

There is no fear of abduction in Tsweleni. On occasion, our group would run into children on their way to school. Most times, the children would recognize us: the American students! They’re still here! They’d run up to us, jump in our arms. We were not strangers—no, we were just people.

One morning, I asked one of our tour guides where the children walked from; she said, “Oh, all over.”

Kidnapping—to village locals—is as strange a concept as alien invasion.

Lauren and I were desperate to change the subject, something lighter. We asked Api and Chadley questions about their life in the village—where in Tsweleni do you live, and do you like living here? Questions asked, but never quite answered. They were far more interested in our lives; they pressed on about America.

“Do you have boyfriends?” Api asked. “American girls always have boyfriends.” He said that last part in a sing-songy voice; a voice that, if I cared to analyze, could easily be mistaken as mocking. I chose not to analyze, only answer.

“No,” I answered quickly, laughing a little. “American men kind of suck.”

“I see,” Api said, nodding a little. “And you?” He looked at Lauren.

“Yes.” Lauren smiled. “Yes, I have a boyfriend.”

“How long?”

“Three years,” Lauren answered proudly.

“Wow,” Api gasped. “And you’re not married?”

“Uh, no, no, I am definitely not married.” Lauren chuckled, glanced unknowingly at me.

We had been warned before we arrived in South Africa that we were likely to disagree on more than we’d agree on—that is, especially regarding marriage customs. But my interest was piqued. I wanted to know how we’d disagree; what did Api think of marriage? What did he think of American dating?

I kept the conversation going.

“What about you, Api?” I cleared my throat. “What’s dating like here?”

“Oh, dating?” Api looked a little confused. “Well, a man cannot marry until he’s a man. So, he must climb up—” Api stopped, looked over his left shoulder, right shoulder, until he found what he was looking for. He pointed forward at a large mountain—one that, to a bunch of American tourists, admittedly looked just like any other mountain.

“That mountain there,” Api continued. Obviously, I realized, it was not just any other mountain. “A boy stays up there for one night. And, when it’s over, he returns a man. Every man in the village has done it. Every boy in the village will do it.”

“I see,” I said, not quite understanding, but wanting to. “So, you can’t date until you’ve climbed that mountain?”

“Yes, and I also need land. And cattle. You can’t propose without cattle.”

“Do you have land?”

“Oh, yes,” Api answered proudly. Later, he’ll show us—a small house, several acres of land. It’s nice, I’ll say; it was a gift, he’ll tell me. He didn’t have to buy it; it was just his. It was always his.

“But still,” Api continued. “I will not marry until I have enough cattle.”

“But what about dating?” I asked, desperate to see if there was even such a thing; it seemed, at this point, that there was only marriage.

“No.” Api shook his head. “I need cows to offer, first. Just like that man back there, who wanted to give you all those cows! I’ll need at least three, four, to give my wife’s family.”

I nodded, if only because I wasn’t sure what else to ask. It appeared we were at another cultural crossroad; Api may never understand the complexity of hook-up culture or serial dating. Selfishly, I envied him a bit.

“So,” Api shifted conversation again. “How many kids will you and your boyfriend have?” He was looking, again, at Lauren.

“Oh, probably only two,” Lauren answered. “I want to be a teacher, and so does my boyfriend. So, we won’t have the means to support more than that.”

“That is not enough,” Api criticized. “Not enough at all. Five, six.”

Lauren laughed. “Not in America’s economy.”

“But, you shouldn’t have to worry about money. That is a man’s job. Your boyfriend’s job. Your job is to raise the children.”

“Well, I want to work,” Lauren answered, as gently as possible. We knew, in that moment, we were entering another cultural divide—this one, though, not as easy to navigate sensitively. Because even though this conversation may have occurred on South African soil, it was not at all foreign to us; to be a woman in South Africa is to be a woman anywhere. And yet, women in South Africa are not always afforded the same privilege as American women. That is, the privilege to politely disagree.

How to politely disagree, I wondered. Can I do that?

Api shook his head dismissively, out of spite or judgement, we couldn’t be sure.

“And what about you.” He spoke to me now. “Don’t you want a boyfriend?”

“Well,” I said hesitantly; at this point, exhausted by the duration of this hike and the conversation. “Not exactly.”

“What? Why?”

“Because every boyfriend I’ve ever had has cheated on me. So, I’m not particularly keen on finding another one right now.”

Api scoffed. Shook his head again. “Well, when are you going to stop trying to find someone who won’t cheat on you?”

And it was here—that sentence—that broke me. I could no longer be patient; I did not want to talk about this any longer. I knew I was instructed by my professors to be polite, mind cultural differences and offer sensitive rebuttal. And, when it came to it, simply agree to disagree. I knew I should’ve done that here—shut down conversation, keep walking on silently. But I didn’t, of course.

“The right one will not cheat on you,” I said, defensive. All the pain I’ve carried up until this moment—the resentment, anger, heartbreak—it spilled out of me. I couldn’t take it back; I didn’t want to.

“You see, you’re wrong. Because a man can still love you and cheat on you. He has needs, you know.” Api kicked a rock. I watched the rock roll far off into the distance, slowing down abruptly as it sunk into a pit of mud. I felt like that rock; I spun and spun and spun, until I didn’t. There was no rolling, anymore.

I had nothing to say to Api; I couldn’t conversate with a man who didn’t want to listen. It was not a conversation we were having anymore, anyway; it was a lesson in patriarchy. I’ve had my fair share of these back in America to know what I was up against.

A wall.

We walked on silently, ignoring Api’s voice. It was all static; I, for the first time all trip, desperately wanted to go home.

**

Later that evening I exchanged a few texts with my father, a political scientist and global studies enthusiast. I was frustrated, to say the least, at Api’s dated narrative of what it means to be a woman. I wanted more for the women in the village: more than washing, cleaning, cooking. I wanted the men here to be held accountable for the instances in which they spoke possessively of their wives or ill-mannered of women we passed on the streets. I wanted to scream when I was told that, of course, all men will cheat on their wives.

“I am treated like an object here,” was the initial text I sent my father. “A body and not a person.”

I explained, in less detail, the conversation I shared with Api that day and the growing agitations I had with other men I encountered in and around the village. I was uncomfortable with the way I was being treated: never addressed by name, never safe enough to walk the streets alone, never seen as the human I am, only the genitalia I was born with.

“Yeah,” my dad texted back. “Question for you: do you need to accept it because it is part of their culture?”

“If there isn’t resistance, there can’t be any progress,” I replied. “Women shouldn’t have to live like this forever.”

“Agreed. But are you imposing western values on a country that doesn’t adhere to those values,” he countered. Thought bubbles appeared on my phone as he typed out the rest. “One might call that cultural imperialism.”

Dumbfounded, I turned my phone off, flipped it face-down, and thought. At first, I thought, “Well, of course he doesn’t get it; he’s not here.” But then, after a beat or two of temporary resentment towards my know-it-all-father (who, I hate to admit, is almost always right), I really thought–had the women I’ve spoken to desired change? Had I spoken to many women at all?

I thought back to the interactions I’d had in Tsweleni thus far. Most, if not all, had been with a local man. If I had spoken to a woman, it was almost always in the company of her husband or some other male relative—the only exception being the three women who hosted our group in their home for two nights. And yet, only one spoke outwardly about her wishes for a more inclusive South Africa; though, not feminist speaking, but rather, racially, economically, socially.

Apartheid reigned in South Africa from 1948 until 1994, when Nelson Mandela was elected. In simple terms, the Apartheid was an all-white government that enforced the racial segregation of all whites and non-whites in South Africa. It dictated that the non-white population, encompassing a majority of South Africa, was to live, work, shop and function in an entirely different space from its white population. And although the Apartheid’s regime had a clear start and end date, racial segregation had existed long before its official political recognition and the effects of such segregation lingered long after their demise.

The people in Tsweleni, and even those in the larger cities like Johannesburg and Cape Town, now must work tirelessly every day to reverse the damage Apartheid reeked on their country. Whether it be by continuous re-election of Nelson Mandela’s African National Congress (ANC) that once defeated South Africa’s greatest enemy or by compulsion towards political redirection, people desire solutions; people desire change.

My professor, Glen Retief, a native South African, later let me pick his brain about the subject. A feminist revolution, I said. How wonderful would that be?

“Yes,” he agreed. “And the women I’d spoken to in Tsweleni are definitely on the same page. But, you must remember, it’s important to these women that it be their efforts that get them there. Does that make sense? But what you’re saying—it’s not cultural imperialism, necessarily.”

I nodded my head, I think, finally understanding. I know what it’s like to be a woman, but I’ll never know what it’s like to be a woman living in South Africa.

**

“You know,” the man with the baby continued after successfully lulling his daughter back into silence. “I don’t trust Americans either.”

“Oh,” I said, my face reddening. This was a moment, among many others, where I didn’t only recognize my privilege, but I was my privilege—I, I realize, am always my privilege. I didn’t have to tell him I was from America for him to know, and I certainly didn’t need to feign my innocence. Why was he to trust me when he knew nothing about me?

He laughed at me again, and, without pause, he explained:

“Because, when you get uncomfortable over here,” he gestured at the sky, over the ocean and across the mountains. That world, as unfamiliar to him as South Africa once was to me. “You all can go back over there. But not us. We don’t leave.”

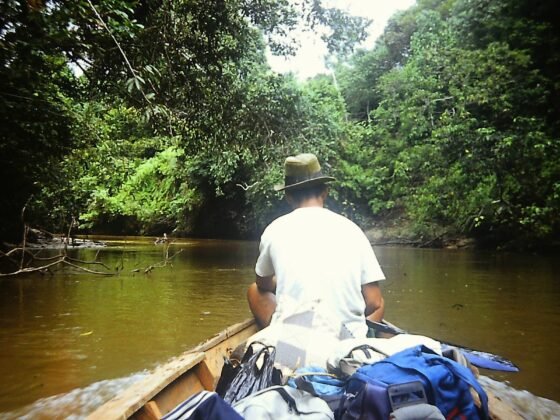

Photo by Gregory Fullard on Unsplash