by Tamsyn Chandler

PureTravel Writing Conpetition 2024 – Longlisted

A palate sourced with clay and dirt from Mars would have rendered perfectly the fields and land ahead of the bus. Most of my fellow travellers were from Madrid, but, I believe, there was a couple from Padua. The roads were smooth, there was a familiar mass of brush that I had passed on the way there, in the taxi from the airport, and aside from the same weathered old man in a long linen robe gently ferrying his goats through the branches and occasional trash blown over from the beach, there was a camel and her child, leant down in the reddish brown Earth, their eyes soft and black, movements slow and safe from harm. Row upon row of dry conifer shielded them from the sun, which wasn’t too harsh, this early in the Spring. The surfboards gave way to roadside ceramicists, then walled universities, their doors hidden from the traffic, and then nothing. A thousand argan trees. Then more, and yet more.

We alighted at the side of the road. We were far, now, from Essaouira. The surf boards, and burnt espresso, small horses running up and down the beach, the men with their arms outstretched, Mogador behind a thin veil of whipped sand and salt, the sounds of the Medina far off, save from the Senegalese drum troupe, and the archipelago of Madeira somewhere, out there, if you threw yourself out to the North.

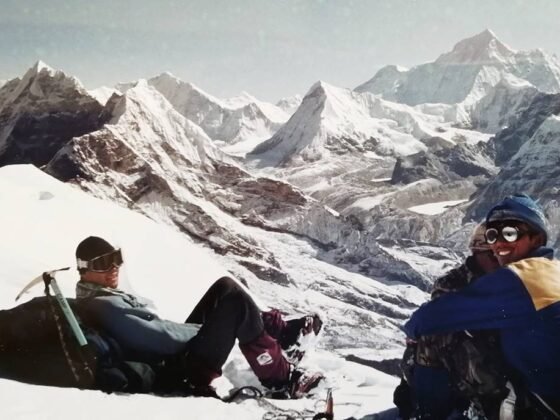

This was my first time travelling on my own in North Africa, although I had trekked in the Atlas Mountains before. Come evening, I regrettably had to return to Marrakech and to the hotel, to friends and family, the taste of fresh walnuts still on my tongue, the sound of the waterfall still in my ears. Ever since then, I had craved it. I had dreamt of it. And Essaouira seemed such a good launch pad to explore the rest of the region from. Dakar in Senegal was an option, too, but travel was too expensive. And besides, I liked the way Essaouira sounded on the tongue, moving along and into the world like a wave, the word itself like the hiss of steam in the pipes, of water approaching the shore. I met the tour guide at the great gate into the walled city. She stood outside the Medina in a backpack, her French so soft spoken as she whispered to us once we arrived about aqueducts as she would bend down to touch the shell of an argan nut.

After a while walking, we arrived at a building complex. A school, layers of wooden palettes, the sound of roosters that can’t be seen, palls of unemptied water. We walk into one part of the building, and then another, then another, each room getting smaller and smaller. And then, a tomb within a tomb. A box of stone, covered in sheets designed to let water fall and run down the sides, and handfuls of sugar thrown here and there.

I hear the word Marabout, and word association takes me to perhaps a small fruit, something akin to a plump, sweet nectarine. A cherry on the rim of a Birthday cake, or a little girl in ribbons with her ankles together, hands behind her back. The tomb itself funnily enough matches this colour scheme. The walls, despite the disarray inside, are painted in shades of mint, pea and apricot, pale champagne pink, like the soft suede underside of a ballet slipper.

But, no, my ignorance, no matter how fanciful, has misinformed my intuition. The Marabout is a figure descended from the Prophet Muhammad (Peace be Upon Him), a prominent member of society since the arrival of Sufi brotherhoods from the Maghreb in the 15th century. Mystics, judges, priests, sometimes all at once, with expansive knowledge of the Quran that ensure an esteemed reputation within their communities. And so, this building. A sawiya, a Sufi mausoleum, a school, a monastery, all of these things at once?

Sufism seeks to attain direct personal experience to the divine. But what is that divinity? Does it take a shape, or a temperature? Usually, one thinks of a goal, and then seeks it out. And yet, at this point, I feel I am attaining something unknown to me, something as of yet unascertained. I would have liked to have seen dervishes, yes, certainly. I would have liked to have seen their long conical hats, and the robe trailing down and around as they move in holy circles. The idea of meditation through active, repetitive movement, the concentration on a learnt choreography as a form of prayer, is not something unfamiliar to me. It is, as far as I’m concerned, above swimming (which involves water and is therefore very holy), as the ultimate communication with, well, what exactly? A boy outside is sitting on an unfinished brick wall playing a sintir. It is carved out of a large, solid piece of wood, and a smooth camel skin that hardly bristles whenever he brushes against it. I make a note, once I am hopefully in Cairo this Winter, to seek out whirling dervishes, and to watch them.

After walking for another couple of miles through the Argan fields, we rested at a woman’s walled house for bread, peanut sauce and mint tea. I wonder, do her grandchildren attend the sawiya? Do they all live nearby, or is she out here, brewing mint tea, tasting its sweetness for group after group of travellers? Everything is covered in white lace sheets. We sit on the floor, cross legged, and she sits a little off side, pouring the tea, increasing in its greenness with each brew, from silver pot to silver pot, the spots long and curled. When I tell her that she has a beautiful sage shrub growing in a tiled circle at the centre of the courtyard, she immediately goes out, and rips off a large leaf for me to press and keep in a book, as a gift. The smell, on arriving back to London, is still strong and herbal and clean.

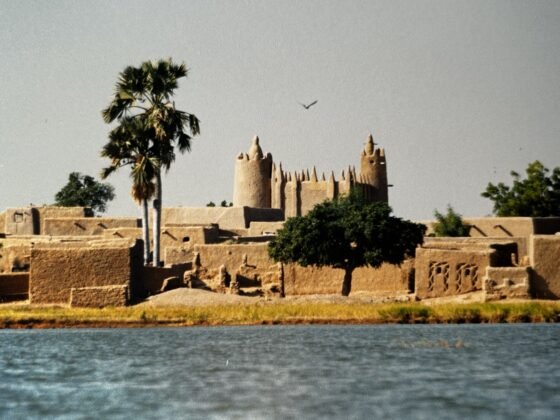

We return the way we came. A kid in blue robe and white hat leans against the doorway, watching us all leave. He moves his leg to rest on the other, and folds his arms. As we drive away from the countryside, the modern world makes itself known through the motorcycles that ride the large sand dunes facing sea ward, the dust being thrown up and roundabout, obscuring Mogador. Something, somehow, had changed within me. That evening, despite my lack of funds and time, I started to research routes that would take me to Dakar, a place that on the map seemed ever so close to that city of my dreams, which was Bamako, Mali, with its buildings like honeycomb and its music, unlike anywhere else in the whole wide world.

Photo by Thiébaud Faix on Unsplash