by Rebecca Rose

Longlisted in the PureTravel Writing Competition 2023

In Central Asia, there is a place called the ‘City of Stones.’

It has been called this since the eleventh century though the city has existed long since before then. In the thirteenth century, it was conquered by the great and terrible Mongolian leader, Genghis Khan, then later by Russia, then after many years declared the capital of Russian Turkestan. The fabled Silk Road made its winding way through this city, marking it forever amongst the mysterious and far-away places we think of as the ends of the earth. In World War II, it became an evacuation center, providing a haven away from the bloodshed and gunfire, and instead offering safety for the leading Russian thinkers in science and culture.

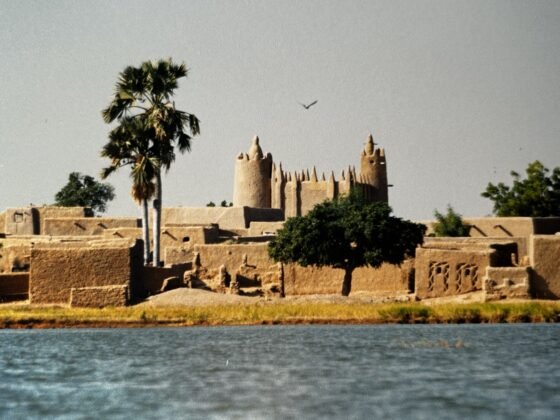

Here, there are ancient reminders of the many people who have come before – marvels of medieval architecture like Kukeldash Madrasah and the Mausoleum of St. Imam Kaffal Shashi. There are palaces, mosques and bazaars, where people walk the same roads that have existed longer than you or I can even fathom. This is the ‘City of Stones,’ once called Chach, once called Binkath. Now, it is called Tashkent and it is one of the oldest cities in Central Asia.

Through its storied lifetime, people have come and gone. You will find many ethnic groups co-existing within Uzbekistan, but there is one unusual group in particular that stands out because of how far they’ve come from their original home. These are the Корё-сарам, or the Koryo-Saram.

At the time when I visited Tashkent, I did not know about Koryo-Saram. Myself, though I am Korean, I had never heard of Koryo-Saram before meeting Anastasia. We met in college and became best friends almost immediately. She was from Uzbekistan but was ethnically Korean. We had so much in common, and yet, there was also much about her that was unfamiliar.

“There are many Koryo-Saram in Tashkent” she explained matter of factly, “I’m 3rd generation Korean. My great, great grandparents were forcefully deported to Uzbekistan by Stalin.”

I stored this astonishing information in my mind.

Our friendship grew and after sophomore year, Anastasia invited me to stay with her family in Tashkent for the summer. Getting to Uzbekistan is no easy feat – the embassy demands documents and addresses, money of seemingly arbitrary amounts, and sends you increasingly indecipherable emails explaining why it’s taking so long. But after a long bureaucratic battle, I was on a plane and landing in an airport largely considered one of the worst in Asia. My luggage was lost and we had to bribe a police officer to let us leave the parking lot. This was the ignominious beginning of a remarkable trip.

I could tell you about the amazing food I ate, the wedding party I attended that lasted a full day and night, the handmade wine from the family vineyard or the local market with baskets of multi-colored spices piled into mounds higher than my head. Or how we rode a raft down a river in the countryside, passing Uzbek people who waved at us and shouted friendly greetings in Chinese, Japanese, Korean, any Asian language, trying to guess what our ethnicity might be. Or when we were stopped by men in black masks and military gear, a threatening-looking group with enormous guns strapped on their backs. (“They are the president’s not-so-secret service,” Anastasia whispered to me in English as the men made a half-hearted effort to search our vehicle. Her mother slipped them some money and they waved us on.) I enjoyed all of these moments (perhaps not the last one) but it’s one moment in particular that I remember the most.

On many mornings, we would wake up late and wander downstairs to find Anastasia’s grandparents entertaining guests. They were usually elderly, friendly types who looked so much like my own grandparents but spoke in Russian. Babushka – grandmother – would already have food set out and we’d join the elders at the breakfast table. Though I could not understand a word anyone said, I loved this feeling of family. One dedushka – grandfather – looked at me curiously and asked me something in Russian. Anastasia replied on my behalf and his eyes lit up.

He said in Korean, “You speak hanguk-mal?”

He spoke haltingly, as though it had been a very long time since he’d used Korean, and the Russian accent was so strong I didn’t recognize what he said at first. He repeated himself, his black eyes peering at me with interest.

“Yes,” I said.

His face split into a wide smile, revealing an impressive array of gold and ivory teeth.

It’s important to know that though Koryo-Saram have carried many Korean traditions and aspects of the original culture through the years, the language they speak in Uzbekistan has been mostly replaced by Russian. It occurred to me that perhaps this really was the first time this dedushka was using pure Korean in a long time.

The moment I acknowledged that I understood him, he clapped his weathered hands together and leaned in.

“Are you from the North?” he asked.

I shook my head.

He shook his, too. “I was there before it was split in two,” he said, “there was no North or South when I was young.”

The others continued their conversations around us, speaking in rapid Russian and laughing together over stories I did not understand. But my attention was only for dedushka. I had never spoken with someone who could remember from before the war.

“How did you come here?” I asked, wondering if he was the son of immigrants from long ago or if he had been deported out of the Russian Far East like Anastasia’s great grandparents.

He sighed and a sort of sorrow settled across his time-worn face. In disjointed Korean, he told me how he came to Uzbekistan. He often used words that I didn’t recognize, a dialect that was no longer spoken in modern South Korea, and sometimes he paused for a long time as he struggled to pull the right word from the depths of his mind where the language of his childhood was hidden.

“I was a soldier for the communists,” he said, “my family lived in North Korea, though it wasn’t North Korea back then. I was only twenty and was being forced to fight. They put me on a truck to go to war, but I didn’t want to leave my family. I had a mother and father and younger siblings. I did not want to die in the war. I jumped off the truck and ran into the forest. Somehow, the bullets did not hit me. I ran and hid for many nights, and escaped into China. I did everything I could to survive…”

Though I could not understand everything he said, his eyes told me the full story.

“Then I met my wife,” he said, glancing affectionately at the old woman seated beside him. She was merrily chatting with Anastasia’s grandmother and eating the fresh cherries we had been enjoying every day that summer.

“She had also escaped. She told me there were Koreans here, where we could make a new life. We came to Uzbekistan together. I have never left.”

“So…” I said slowly, “your family in Korea…?”

He sighed again. I couldn’t help it; this time I sighed too, unconsciously mirroring his heaviness.

“I could not go back for them,” he said, “I do not know if they were killed after I deserted.”

We sat silently for a moment, looking at each other, two people far from home but in very different ways.

“Harabeoji,” I said finally, calling him ‘grandfather’ in Korean, “you’ve wandered far.”

Dedushka smiled, breaking his spell of sadness and said, “I could live a full life, have friends and a family. I am thankful that I’m here.” He leaned in and patted my hand warmly. “You will have a lovely time in Tashkent.”

The summer passed in a rosy blur of hot afternoons napping on the front porch and endless rounds of refreshing cherry kompot. The three months sped by without any consideration for my desires to make it slow down, and soon enough I was once again on a plane, leaving the airport that definitely lives up to its reputation as one of the worst in Asia. As I looked out my window, watching the buildings grow smaller and smaller, I felt both happy and sad, all at once.

“Good bye,” I murmured, looking at the city where a bit of my heart now goes when I think about family and friends.

Just like the many who have come and gone before, I had been a traveler to this place and left my own footprint. In an infinitesimally small way, I had become another part of its legendary history, like Dedushka, like Anastasia’s grandparents, like the Koryo-Saram who had survived and created a new home there.

Inconsequential and tiny as it may be, a little part of myself still exists there in Tashkent, the city that became home for the wanderers. One day, may I wander so far again.

Photo by AXP Photography: https://www.pexels.com/photo/the-blue-domes-of-the-mosque-in-uzbekistan-19439206/