Purnima Unnikrishnan tells us of a trip to the southern Indian state of Kerala and the hidden joys of coconuts. This article was part of the Stories For Survival campaign organised by the UK charity Explorers Against Extinction, of which PureTravel was the sponsor.

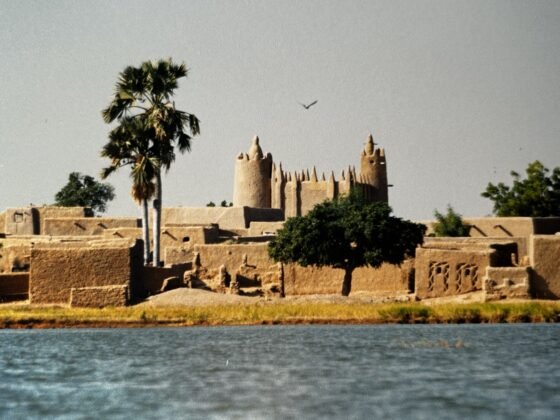

It has been at least ten minutes on the boat, but I’m still in awe and ever so slightly disoriented by the dense placid water around me. The boatman points vaguely to the far right where the bulky backwater we are on meets a canal. That canal empties into some other waterbody way up ahead and so on. Such winding waterways are the crux of Alappuzha, gateway to the famous backwaters of Kerala, a southwestern state of the Indian subcontinent known for its unnaturally beautiful landscapes. The matrix of interconnected canals, lagoons, rivers, lakes and inlets stretches to more than 900 km parallel to the Arabian Sea coast. I feel like I have entered the generous gut of the state. It’s going to be water, water everywhere for the next few hours. I hum with anticipation.

When my friends and I had arrived at Alappuzha earlier today, an overwhelming array of boats moored to the side of the backwater welcomed us. The canvassing and bargaining began, and we got more confused on what kind of boat to choose to explore the waterways. Our initial pick was of course a Kettuvallam. The humongous boats with thatched roofs and wooden hulls are steeped in the history of the land. Made of wooden planks tied up using thick coir ropes, they functioned as cargo vessels. Refurbished, they now serve luxury boating experiences to tourists from around the globe. The bigger ones have multiple bedrooms for overnight stay. However, they can be pricey for the budget traveller. There are government-run boats as well, which are cheap and follow a set route but the seats fill out super-fast, and they can be uncomfortable for long rides. Alappuzha inhabitants rely on these boats for daily commute.

I suggest that we deliberate over fresh coconut water sold on the makeshift carts around us. The vendor deftly cuts off tops of tender coconuts using a machete and thrusts straws into them. After we empty the water, we return the coconuts to him, who hacks at them and uses small sections to scoop out the pulpy insides. By the time we are done gobbling it up, we have made our decision – Shikara boats, which can be rented out on hourly basis. Once you look past the gaudy interiors common to this kind of boat (ours has flashy red carpeting and glittery pillows) one can understand its charm. Unlike the Kettuvallam, smaller boats such as the Shikara are not restricted to the main channels, which means we get to explore more.

Two hours later, we are in a canal lined with countless overhanging palm and coconut trees. Paddy fields and islands on either side are separated by coconut grooves and small gushing streams. A gentle breeze dances with my hair as I lazily observe life on the backwaters. A woman washes her clothes standing waist deep in water. A few kids wave at us. The adults are mostly indifferent; used to the curious tourist gaze I presume. It’s interesting how life has been built around the water. We pass by houses, a school, a government dispensary, several stores and a toddy shop. The signs of urbanisation don’t take away the pristine beauty but I can’t help wondering how long the happy medium will last. Rampant encroachment of agricultural land and illegal sand mining have already begun disrupting the delicate balance, evident from the annual flooding of Alappuzha and Kerala at large in recent years.

Three hours in, the boat is moored to the side of a smaller backwater, and we are headed to a small shack for lunch. No fancy seating and the waiters tell the menu from memory. But the boatman has promised a scrumptious sadhya served on plantain leaves as per Kerala tradition, and he better be right. The restaurant also offers fried and curried fish caught fresh from the brackish waters. The star is Karimeen or pearlspot, the official state fish of Kerala. We get to choose our fish before they cook it for us. We head to the kitchen back of the restaurant to make our choices. Fifteen minutes later, there’s no sign of the food. I can eat the plantain leaves at this point. Mercifully, the food arrives followed by the fish. Everything is cooked in coconut oil, which lends a peculiar aroma. We leave the place with our hearts and bellies full.

Food comas are real. I struggle to stay awake as we head back to our boat, not wanting to miss any moment of what has already come to be a memorable day of my life. For a person who has always struggled with anxiety, it has been difficult for me to stay rooted in the moment. If it’s the stillness of the water that has grown on me, I can’t say, but I feel remarkably calm in this place.

I have lost track of time, but it must be at least two hours since lunch. Our boatman has turned around to get back to the start point. There are early signs of sunset. The billowy clouds have acquired some colouring. I spot some birds sliding through the sky, possibly retiring for the day. Soon the chatter dies and we are silent watching rose gold and peach speckling tips and crevices of everything so that the whole scene is a moment of art. We stop by the coconut water stall again before retreating, and I realise that through the day we have witnessed several manifestations of the humble coconut, be its water, oil or coir ropes. Long before its global appeal in the beauty and health industry, the fruit has ruled life in the region. It’s difficult to think of Alappuzha without coconuts. And it’s difficult to picture a world without alluring places such as Alappuzha. Guess, a world without coconuts would be a sad place.